The story is told of Reb Zusha, the great Hasidic Master, who lay crying on his deathbed. His students asked him, “Rebbe, why are you so sad? Why do you cry? After all the mitzvahs and good deeds you have done, you will surely get a great reward in heaven!”

“I’m afraid!” said Reb Zusha. “Because when I get to heaven, I know Gods’ not going to ask me, ‘Why weren’t you more like Moses?’ or ‘Why weren’t you more like King David?’ But I’m afraid that God will ask, ‘Zusha, why weren’t you more like Zusha?’ And then what will I say?!”

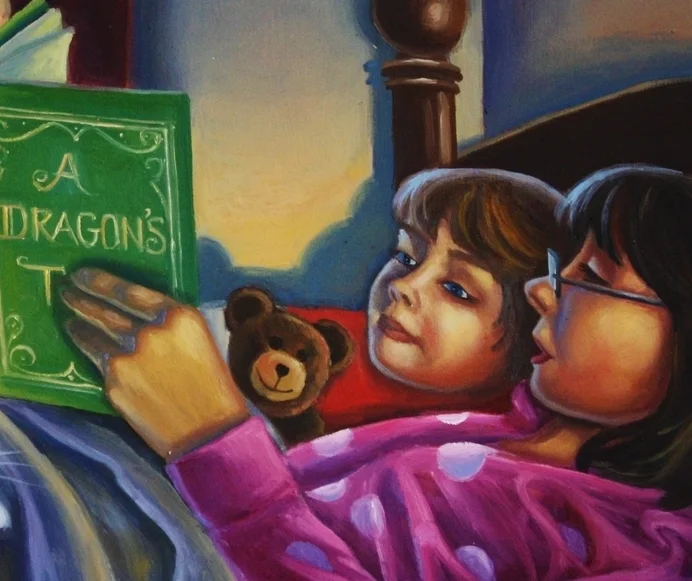

Painting courtesy of Hillary Scott Studios http://hillaryscottstudios.com/

This was a story we discussed in our Jewish Parenting class; and at first the relevance to parenting seemed rather thin on the ground. But a good rabbi is always ready to segue, and fortunately we had one in Sally Finestone of Congregation Or Atid.

“Do our kids have to be Moses?” she prompted. “Or David?”

“No,” came the tentative answer. “There’s already been a Moses. And a David.”

From there it was an easy slide into how each child is unique, how our job as parents is to treasure that uniqueness. A simple lesson, easy to forget and difficult to implement.

A few nights later as I was putting my ten-year-old, champion-worrier son to bed, he said, “I’m afraid I’m not going to be a good grownup.”

I stopped tucking, caught in a hiccup between bafflement and hilarity. Why would my boy worry about something that by the most conservative estimates was eight years away? That happens very gradually? Why would my kid, who taught himself how to read as a toddler and plays piano better with one hand than I do with both but unlike me has never had a lesson, why would he doubt himself this way?

“I’m serious,” he said. And he was.

Which is when Reb Zusha leapt to the rescue. At last! A chance to apply the words of one insecure overachiever to another! I took a deep breath and told my boy the story.

“But did he have to be David?” I said, cribbing shamelessly from our class discussion. “Or Moses?”

“No,” said my son.

“Of course not,” I agreed. “Those jobs are already taken. And the Torah even tells us there was never again anyone like Moses—or before. So the only job you have, my friend, is being the best you you can be. Not ten years from now, but now.”

He ruminated. I pressed my advantage.

“Have you been the best you today?” I said. “Did you do a mitzvah?”

He nodded eagerly, and we chatted about his several recent good deeds. By the time I left he was serene and sleepy.

You know that boss you had or have, the one who only criticizes, never compliments? It’s easy to be that parent. We figure people already know when they’re doing the right thing; or that no one deserves kudos for doing what they’re supposed to do anyway. But it’s not that simple. Rabbi Abraham J. Twerski says, “Too often we take our children’s good behavior for granted, and react only to their misbehavior. Let us remember the Torah teaching that God rewards us for what we are supposed to do. Let us be more alert to ‘catch’ our children doing good, and reward them for it, even if only with a smile or a brief compliment…. Positivity gives both parents and children a more joyous perspective on life.”

Nowadays my son and I have our “best you” discussion most nights. I get to hear about the loving acts he has done, that he is rightly proud of. He goes to sleep with a smile on his face, and as for me—well, I may not be David or Miriam, and I can’t claim to be the best mom; but for a few brief moments of giggly chat with my firstborn, I am the best me I can be.

This post first appeared in the June 26th issue of Adult Jewish Learning.